The artist-in-residence at the British Institute of Radiology (BIR), Hugh Turvey, sees beauty in error. Speaking at a recent BIR networking event, "Curious World of Radiology," Turvey explained how radiography informs his work as an artist.

Hugh Turvey, artist-in-residence at the British Institute of Radiology (BIR).

Hugh Turvey, artist-in-residence at the British Institute of Radiology (BIR)."Many people view radiography as the truth, and what they see on an x-ray is considered the truth," he said. "But much of the image from an MRI or a CT scan is computed and it's open to interpretation, and by extension, to error."

It is this opportunity for error offered by the radiographic film process that fascinates Turvey.

As a photographer/art director, he fell into the field of radiography by chance. Twenty years ago, whilst working as a music industry photographer, he visited the Royal Free Hospital in London in search of an image of a bone for an album cover.

"I met the head of radiology over lunch and found myself introduced to a world of large film, big processing, a light source that was invisible effectively, and a whole other way of seeing the world. This was visual revelation and a career turning point," Turvey reflects.

A couple of hours later, he left the hospital with armfuls of radiographic film, something unlikely to happen today.

"I love the aesthetic of pushing something with a 'light' that was different, in an arena that was different, with different physics," he said.

There is something much deeper in the substrate beneath, Turvey said. Here is an example of sage. All art images courtesy of Hugh Turvey.

There is something much deeper in the substrate beneath, Turvey said. Here is an example of sage. All art images courtesy of Hugh Turvey.He explained that working with analog film, as Turvey does ("I never touch digital"), is prone to error, and therein lies the attraction. "There are happy accidents, and visual information obtained on x-ray film is open to interpretation and can be played with, used experimentally," he said.

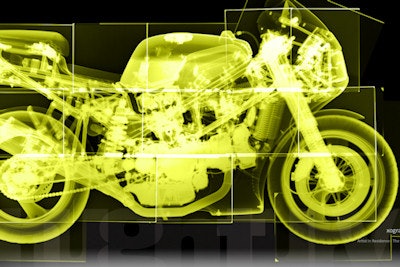

Turvey sheds light on his concept of using the error in processing and interpretation with an example of an image he created of a Ducati 888 motorbike. The bike was exposed in sections and later merged using a digitizer, usually used for medical film.

Ducati 888, an image created by Turvey. The bike was exposed in sections and later merged using a digitizer, usually reserved for medical film.

Ducati 888, an image created by Turvey. The bike was exposed in sections and later merged using a digitizer, usually reserved for medical film."We were astounded that when amalgamated nothing actually married up. The reason for this is that the film is pulled unevenly through the digitizer and this introduced an error," he said. "We had to manipulate the whole image to reassemble it correctly. These sorts of errors started me thinking."

In addition to harnessing the artistic potential of error in the radiographic analog film process, Turvey remarked he wants to push the aesthetic of the natural world, "see deeper and understand more about the fabric of our existence," adding, "If I know what fabrics and structures make up an object then when I see the object I tend to think in those terms rather than just surface. There is something much deeper in the substrate beneath."

Ultimately, Turvey pointed out that he liked to play with the potential for thinking about the world differently, "not just viewing it as it is and making a judgement based on that, but be more investigative with the process."

Shoes inside the suitcase of "Mr. and Mrs. Smith."

Shoes inside the suitcase of "Mr. and Mrs. Smith."He hopes that advances in imaging technology and continued collaboration with the radiographic industries will help drive artistic ambition and the radiographic aesthetic.

In addition to his exploratory role, as artist-in-residence at the BIR he is required to engage in a degree of outreach work. At the U.K. Radiological Congress (UKRC), Turvey carried out a project aimed at school children, helping them generate images by placing an object on UV-sensitive paper and then directing UV light at it. It was meant to simulate x-ray. Sunglasses were used to protect the children's eyes from the UV light and to stimulate a discussion on radiation protection, density, exposure, and physics.