CT tends to underestimate cardiac metastases in malignant melanoma patients, and to reduce morbidity and mortality in these cases, awareness is essential of different types of cardiac metastases and their characteristic appearance on CT, German researchers have found.

"Due to prolonged survival and technical advances in CT imaging, cardiac metastases in patients with malignant melanoma are observed more frequently nowadays," Dr. Tanja Zitzelsberger, a fourth-year resident in the department of diagnostic and interventional radiology at Tübingen University Hospital, told delegates at the 2017 meeting of the European Society of Cardiovascular Radiology (ESCR) congress in Milan.

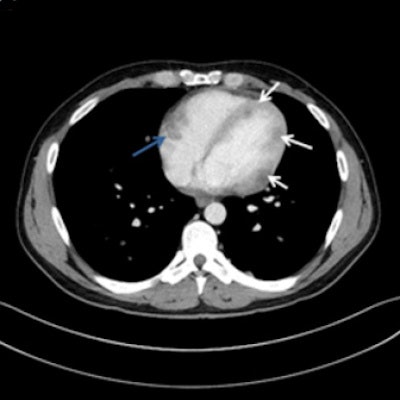

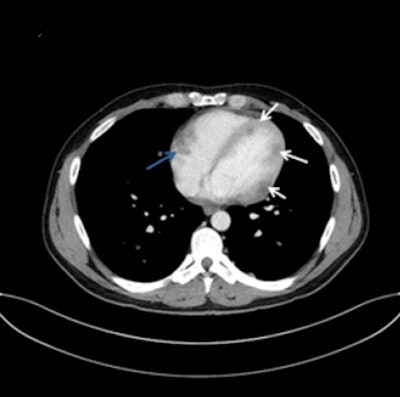

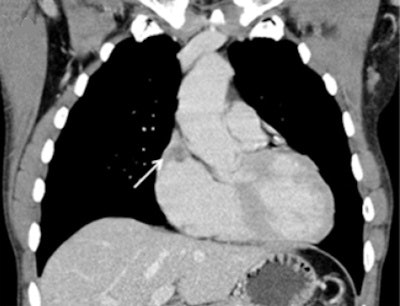

A 32-year-old man with multiple myocardial metastases (white arrows) as well as endocardial metastasis located in the right atrium (blue arrow). All images courtesy of Dr. Tanja Zitzelsberger and published in Cancer Imaging (1 July 2017, Vol. 17:1, pp. 19).

A 32-year-old man with multiple myocardial metastases (white arrows) as well as endocardial metastasis located in the right atrium (blue arrow). All images courtesy of Dr. Tanja Zitzelsberger and published in Cancer Imaging (1 July 2017, Vol. 17:1, pp. 19).Cardiac metastases can involve every part of the heart, and developing awareness of different types of cardiac metastases and their appearance on CT is necessary for further investigations, and may contribute to targeted therapy, she continued. These metastases often affect patients with aggressive subtypes of malignant melanoma in a progressed state of disease, and depending on localization and size of cardiac metastases, surgical resection or anticoagulant therapy must be considered.

Cardiac metastases are rarely detected in routine staging examinations in patients suffering from malignant melanoma, Zitzelsberger said. One reason is most cardiac metastases remain clinically silent, while another reason is cardiac metastases may evade detection in whole-body CT due to motion artifacts. However, cardiac metastases are frequently described in autopsy studies, with an incidence of between 2% and 18% in patients with advanced malignant tumors. In contrast, the detection of cardiac metastases in vivo is less than 1%, suggesting that despite being rather frequent, most cardiac metastases are only diagnosed postmortem.

The Tübingen approach

To refine its care for these patients, the researchers decided to assess the anatomic distribution as well as the morphologic and histologic appearance of cardiac metastases from malignant melanoma.

Dr. Tanja Zitzelsberger.

Dr. Tanja Zitzelsberger.They analyzed the radiology database to identify melanoma patients diagnosed with cardiac metastases at routine oncological imaging. In total, 2,726 patients were screened from May 2006 to August 2016. The group reviewed the histological results and patients' hospital files, including imaging reports and tumor markers (lactate dehydrogenase and S100-protein).

The examinations were performed on various systems (Somatom 4/16/64, Somatom Definition AS, and Somatom FLASH [2 x 64 slice], from Siemens Healthineers). The technical parameters were 250 to 330 mm field-of-view with 512 by 512 reconstruction matrix, 120 kV, 100 to 150 effective mAs, and tube rotation time of 0.5/0.3 ms. The CT scans were reconstructed with 3 mm slice thickness coronal and 5 mm slice thickness axial using a soft-tissue kernel. Patients received intravenous contrast agent (Ultravist 370, Imeron 400), 2 ml/s, 80 to 120 mL, adapted to body weight.

Zitzelsberger and colleagues evaluated 25 patients with known metastasized melanoma and an incidental finding of cardiac metastases during routine staging CT. They assessed images for the presence, localization, and extent of cardiac metastases by two experienced readers (3.5 and 15 years of experience in oncological imaging). These were either classified as pericardial metastases, as endocardial metastases, or as myocardial metastases.

Metastases along the endocardium with polypoid growth into cardiac cavities were classified as endocardial metastases, and these patients were assigned to group 1. Metastases located in the myocardium with infiltrative growth were classified as myocardial metastases, and patients were assigned to group 2. Patients with metastases of the pericardium were assigned to group 3.

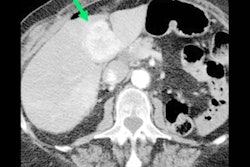

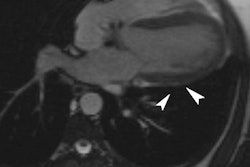

A 52-year-old man with endocardial metastasis located at the junction of vena cava superior. The patient was assigned to group 1.

A 52-year-old man with endocardial metastasis located at the junction of vena cava superior. The patient was assigned to group 1.Fourteen out of 25 patients presented with singular cardiac mass (56%), whereas 10 patients (40%) presented with multifocal metastases, and one patient with disseminated metastases. Twelve patients presented with endocardial (48%), eight with myocardial, and two with pericardial metastases. The most frequent site involved in endocardial metastases was the right atrium (67%), followed by the right ventricle (33%).

To assess the general tumor burden, the group compared the number of involved organs between the patient groups, as well as the calculated tumor burden score. They defined potential sites of metastatic spread: liver, lung, lymph nodes, intestinum, bone, brain, soft tissue, and other. The tumor burden score for semiquantitative assessment of tumor burden was defined as follows: one point for one to two metastases per organ, two points for three to five metastases per organ, three points for more than five metastases per organ.

There seems to be a correlation between histological subtype and location of the cardiac metastasis, according to the researchers. Median survival after diagnosis of cardiac metastases was eight months, with no significant difference regarding the localization of metastasis within the heart. Lung metastases were present in 56% of patients with involvement of the left ventricular endocardium and myocardium. Also, they found a slightly higher tumor burden in patients with pericardial metastases or metastases in more than one compartment, but with no statistical difference.

Editor's note: The scientific posters from the ESCR 2017 meeting are available in the European Society of Radiology's EPOS database. To view the presentation by Zitzelsberger and colleagues, click here.