Numerous studies examining the effectiveness of lung cancer screening programs have led to government recommendations for coverage for lung cancer screening across parts of Europe and the U.S., but doubts persist, particularly concerning the potential harm from radiation dose, recruitment strategies and criteria, and other logistical issues.

In an opinion piece posted on 2 April by Archivos de Bronconeumologia, authors Prof. Alberto Ruano-Ravina, professor of preventive medicine and public health at the University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, and Prof. Harry J. de Koning, deputy head and professor of public health & screening evaluation at Erasmus MC in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, debated the pros and cons of implementing lung cancer screening programs in Europe.

Ruano-Ravina and de Koning lead off with the most compelling argument for screening: The findings from clinical trials show that CT screening for lung cancer substantially reduces mortality in high-risk individuals. They noted that findings from the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) in the U.S. showed an 8% LC mortality reduction for men and 22% for women in the eighth year of follow-up, whereas the NELSON trial from the EU showed a 24% mortality reduction for men and 59% for women in the same follow-up period.

The authors noted that modeling by lung cancer subtypes shows that mortality from screening-detected stage I lung cancer is reduced by 65% to 85%, that “[i]n the Netherlands (18 million inhabitants) a rather stringent LC [lung cancer] screening program may ultimately prevent 1,000-1,500 LC deaths annually, which resembles the present breast cancer screening program.”

They also acknowledge two important concerns with screening cited in systematic reviews: i.e., false-positive referrals and overdiagnosis (diagnosing lung cancer in individuals dying from another cause before the cancer would have become clinically apparent). These could be mitigated through the use of more stringent approaches and criteria, they believe.

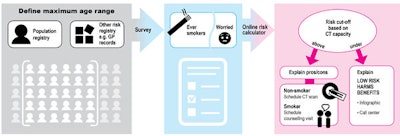

Recruitment method. Image courtesy of Prof. Alberto Ruano-Ravina, Prof. Harry J. de Koning, and Archivos de Bronconeumologia.

Recruitment method. Image courtesy of Prof. Alberto Ruano-Ravina, Prof. Harry J. de Koning, and Archivos de Bronconeumologia.

For the question of recruitment strategies, the authors pointed out that some screening programs have succeeded in recruiting at-risk groups: “Successes are likely the consequence of good governance, available digital registry systems, and a targeted recruitment method.”

While the authors referred to the offer of a smoking cessation program as a benefit to screening for high-risk groups, they also highlighted that such programs are limited in effectiveness; they added that one study determined that in older patients, the screening proved more efficacious than smoking cessation programs in lung cancer prevention programs.

“We have not yet found the best approach in this respect, and feel ethically obliged to offer effective smoking cessation interventions, perhaps by standard pharmacological means,” they wrote.

Cost-effectiveness and resource allocation

Another advantage of screening programs is the financial benefit: while screening programs may be expensive to implement, treatment costs for advanced lung cancer—again, most often diagnosed in late stages—are very high, they explained. Costs for screening may also be reduced considerably if it can be determined that longer intervals between screening are appropriate depending on risk level, they commented.

Where the disadvantages lie, the authors wrote, is in large part due to the lack of resources. With an aging population, the demand for services has grown, and wide-scale lung cancer screening programs put a burden on skilled radiologists, who are limited in number. Additionally, CT machines themselves cannot be dedicated easily to one purpose, and any positives in lung cancer screening require radiological follow-up for confirmation, as well as potentially periodic scans. The burden on both staff and equipment to implement a wide lung cancer screening program would be considerable, they added.

Ruano-Ravina and de Koning also pointed out that the nature of the burden of the disease would change: with earlier diagnosis of high-risk individuals, different groups would still be less likely to be diagnosed: “Never-smokers, long-term ex-smokers, light smokers, and those younger than 50 years or older than 80 would not be detected. Small cell lung cancer has to be added, since early detection has proven ineffective,” they noted, adding that their concern is that screening programs might still miss a significant number of lung cancer cases.

One of the greatest concerns with public health programs is determining where funds allocated will do the greatest good for the most people. They wrote that in preventing lung cancer, it’s undeniable that smoking cessation — or encouraging people to never smoke — does the greatest good (and also prevents other conditions.) The money spent on screening might be better invested in smoking cessation programs in some EU countries where smoking rates are still high, they added.

The authors concluded that while the evidence supports the benefits of lung cancer screening programs, they should be accompanied by smoking cessation programs. To make screening worthwhile, they recommend careful and clear governance of any such programs and targeted recruitment.

Read the full article here.