Breast imaging organizations and political bodies are criticizing updated guidelines on breast cancer screening by the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC).

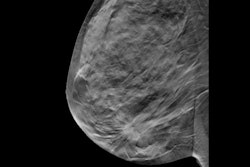

Released on May 30, the task force’s draft guidelines recommend that women between the ages of 40 and 49 should not be systematically screened. Instead, these women are advised to have informed conversations with their primary care provider and make their own screening decisions from there. Additionally, the guidelines do not recommend supplemental imaging in women with dense breasts or women with a personal family history of breast cancer.

“There’s so much misinformation out there, so we want women to be able to advocate for the screening they need, to know that breast cancer can happen at any age,” said Jennie Dale, co-founder and executive director of Dense Breasts Canada. “We’re hoping to get clear information out to women that they really have to look after themselves because with the state of confusion, it can be difficult.”

Dense Breasts Canada is a nonprofit organization dedicated to raising awareness of breast density and advocating for best practices in breast cancer screening.

The CTFPHC’s updated guidelines differ slightly from the guidelines issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) in April. The U.S. guidelines recommend biennial breast cancer screening for women ages 40 to 74, a grade B recommendation. The USPSTF also said that there was insufficient evidence to recommend supplemental screening with MRI or ultrasound in women, regardless of breast density.

These drew criticism from radiologic societies such as the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the Society of Breast Imaging (SBI), among others, which recommend annual screening starting at age 40 and with no age limit. The societies’ guidelines recommend that women, especially Black and Ashkenazi Jewish women, receive a breast cancer risk workup by the age of 25.

Paula Gordon, MD, from the University of British Columbia, said that while the CTFPHC included observational studies, systematic reviews, and modeling in their decision-making for the updated guidance, the task force is “obsessed” with randomized controlled trials.

“So, when they looked at these outcomes, they gave greater weight to those 40- to 60-year-old randomized trials than to the modernized observational studies, said Gordon, who is also a volunteer medical adviser to Dense Breasts Canada.

Gordon added that the guidelines could make way for more interval cancers diagnosed at advanced stages in younger women.

And Dense Breasts Canada may have an ally in Health Canada, the Canadian government’s department that is responsible for national health policy. In a May 30 statement, Mark Holland, the country’s Minister of Health, released a statement outlining steps to address the “serious concerns” regarding the task force’s findings.

Holland invited breast cancer experts to review the draft guidelines and share their critical analysis and called for the public consultation period from six weeks to a minimum of 60 days. He has also asked the Chief Public Health Officer to convene the senior provincial and territorial officials and key experts to review the guidelines and to share their best practices.

Holland also asked the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) to advance the launch of an external expert review that will examine the CTFPHC’s processes and provide recommendations to improve the task force’s processes.

“It is important that Canadians trust the process of public health guidance. Public health guidance must protect Canadians,” Holland said. “That is why I am taking these actions today to make sure that Canadians have the resources they need to keep themselves and their loved ones safe and healthy.”

Dale said she hopes that Dense Breasts Canada will be able to work with Health Canada in these consultations.

“This is an issue that has the support of all the different parties in Canada,” she said. “We hope to work with everyone on it. It’s nonpartisan. They are all interested in the best screening for Canadian women.”

Gordon said that in the meantime, women in Canada should go to their doctor if necessary to get a requisition to have their mammograms “ideally every year,” or every two years if they live in a province that goes by biennial screening.

“If you’re in good health, keep having mammograms as long as you’re allowed to without a requisition, and then get a requisition,” she said. “There are loads of women in their early and mid-80s who are in excellent general health. If they get breast cancer, it would be best to find it early.”