PET scans, either on their own or in combination with MRI, provide an anatomical overview of dementia patients' brains. They also offer precise molecular information about the nature and extent of the disease -- even at an early stage. This is valuable both in clinical research and patient care, and should be a normal part of the imaging professional's repertoire, according to Dr. Henryk Barthel, professor of nuclear medicine clinic at Leipzig University Hospital.

"Brain imaging needs to become a standard part of dementia diagnosis," he said, pointing out that imaging is a reliable way of identifying other diseases associated with cognitive impairment, such as circulatory disorders, inflammation, and tumors. "It also helps in precisely diagnosing dementia by showing which areas of the brain are affected, and the molecular properties of the changes."

PET reveals diseased protein in the brain

MRI is the most common diagnostic procedure for dementia. It allows radiologists to measure the volume of specific parts of the brain, such as the hippocampus, and thus to identify Alzheimer's and other dementias. "PET is more precise and sensitive because it provides information about molecular processes in the brain," said Barthel, who spoke on the topic on the opening day of the 99th German Radiology Congress (Deutscher Röntgenkongress, RöKo 2018).

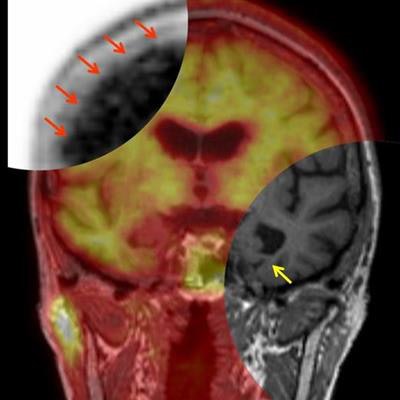

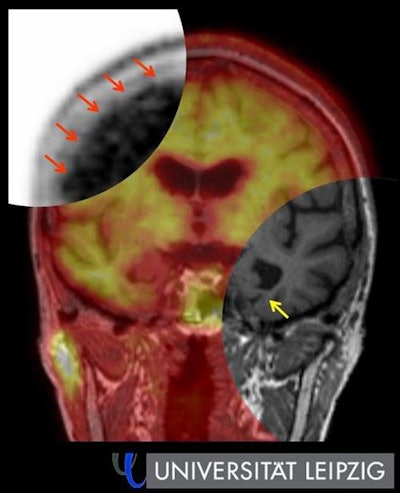

Hybrid amyloid PET/MRI in Alzheimer's disease. Top left: Evidence of amyloid plaques in the cerebral cortex (red arrow) using PET. Bottom right: Signs of hippocampus shrinkage (yellow arrow) with simultaneous MRI. Image courtesy of Leipzig University.

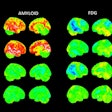

Hybrid amyloid PET/MRI in Alzheimer's disease. Top left: Evidence of amyloid plaques in the cerebral cortex (red arrow) using PET. Bottom right: Signs of hippocampus shrinkage (yellow arrow) with simultaneous MRI. Image courtesy of Leipzig University.Traditional FDG-PET reveals glucose uptake and thus the tissue's energy metabolism, while amyloid PET, which has been the subject of extensive research for some time now, is more helpful in dementia diagnosis because it reveals the amyloid protein deposited in the brains of Alzheimer's patients. "This allows us to see the disease years before brain volume starts to decrease and to better distinguish Alzheimer's from other forms of dementia."

New PET processes provide even more precise data

Barthel said the future lies in a hybrid of PET and MRI. "Combined imaging using both techniques gives us a detailed picture of the anatomical and functional aspects of dementia. It's particularly suitable for routine clinical use because patients only have to visit once and we get all the key data we need from the examination."

Dr. Henryk Barthel

Dr. Henryk BarthelAnother new method that is gaining ground is tau PET, which shows the tau protein that accumulates in Alzheimer's and certain other neurodegenerative disorders. The protein is closely correlated with the progress of the disease and allows very precise statements about the staging of neurodegenerative dementia.

The use of PET in viewing brain receptor systems in dementia is also being intensively researched, with a particular emphasis on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. One such study is being carried out by Dr. Osama Sabri at Leipzig University Hospital. The receptor density decreases significantly, particularly in Parkinson's-related dementia. "This can be seen with PET, and this form of PET can be used to assess the effectiveness of experimental therapies, for example those focusing on nicotine receptors," he noted.

Adding value to research and clinical care

Centers that offer PET for dementia patients also use it as an important component in clinical studies of new therapies, and amyloid PET could also be more widely used in routine clinical care, according to Barthel. "The three classic indicators for this imaging are early diagnosis in patients with mild cognitive impairment, differential diagnosis of existing dementia to establish whether there is underlying Alzheimer's, and memory disorders in people under 65."

One problem in Germany is that amyloid PET is not routinely funded and he thinks this must change. Several current studies of large patient groups are intended to show that amyloid PET imaging is beneficial in dementia care.

RöKo 2018 takes place at the Congress Center in Leipzig from 9 to 12 May.

Editor's note: This is an edited version of a translation of an article published in German online by the German Radiological Society (DRG, Deutsche Röntgengesellschaft). Translation by Syntacta Translation & Interpreting. To read the original version, click here.