Radiologists must keep in mind the underlying causes of diagnostic errors in CT in the emergency room (ER), focusing on critical diseases that are easy to overlook, and constantly be aware of the risk of oversights and master specific methods to avoid them, according to award-winning researchers.

There are some situations in which accurate diagnoses may not be achieved in the ER due to various factors, such as the presence of nonspecific clinical presentations or the use of noncontrast CT in cases when contrast-enhanced CT should be used, noted Dr. Kumie Miyakawa and colleagues from St. Marianna University School of Medicine, Kawasaki, Kanagawa, Japan. Their 10 tips to avoid oversights are as follows:

- Windowing: Adjust window level and width a little stronger to optimize visualization of borders between structures, air, bone, and pathologies like acute thrombus and hematoma.

- Multiplanar reconstructions (MPRs): They can reveal findings that are not evident on axial images.

- Thin slices: They make it possible to find even small abnormalities or subtle changes.

- Checklist: Make a list of diseases you do not want to miss and use it every time you report an exam.

- Mechanical survey: Track down organs and structures to find abnormalities from top to bottom without thinking of certain diseases.

- Top and bottom slices: Stay alert even at the top and bottom of the CT slices.

- Indirect findings: Look for not only direct findings but also related ones to the diseases.

- Interval change: Try to study a case again with a time interval or compare it with previous exams. This can identify changes over time or subtle findings that may have been missed in a single study.

- Contrast enhancement: Administer contrast agent to assess blood flow in inflammation or organ ischemia and active bleeding in hemorrhagic pathologies.

- Consider another modality: MRI can be more sensitive, especially in central nervous diseases.

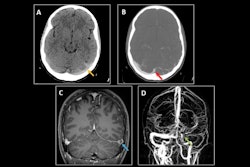

By narrowing the window setting in suspected cases of subarachnoid hemorrhage, the findings become easier to see and they can be identified more easily in the bottom slice, Miyakawa and colleagues explained in an ECR 2024 poster that received a certificate of merit. "Look at the images thoroughly. Compare with past images to identify subtle changes."

A low-density area may be seen in the right cerebellar hemisphere, and this corresponds to the area of anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA), indicating a cerebellar infarction. Even a faint focus of infarction can be detected by adjusting the window level and width with an awareness of anatomical vascular territory. "Narrow the window setting when reading a head CT to check for infarct focus along the vascular territory," they recommend.

In cases of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, by narrowing the window, high-density areas can be detected in venous sinus. With contrast enhancement, the area becomes dark, which indicates thrombosis. When high-density area is seen within the venous sinus on a noncontrast CT, consider differential diagnoses such as postcontrast agent use or dehydration. When there is infarction or subcortical hemorrhage, the signs of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis should be checked for because it's rare, according to the authors. Always look for high-density in the venous sinus in noncontrast CT.

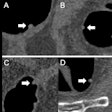

"When a patient complains of neck pain or back pain, the focus tends to be on vascular disorders such as vertebral dissection or aortic dissection. However, it's crucial to pay attention to intraspinal abnormality," they continued. "By windowing, hemorrhages become whiter, while other normal structures within the spinal canal are dark. Sagittal reconstructed images should be created not only under bone setting but also under soft tissue setting. In most cases, MRI reveals epidural hematoma more clearly."

Pay attention to intraspinal construction and detect the hemorrhage by windowing and using MPRs, they added.

In general, contrast-enhanced CT is used to diagnose pulmonary thromboembolism, but fresh thrombi may appear as a high-density area in noncontrast CT, and they may not be visible with a usual window setting, so it's important to use a narrow window setting to identify thrombi, the authors noted. Artifacts can also appear as high-density areas, making it difficult to distinguish. It's also important to evaluate indirect findings, such as inferior vena cava (IVC)/right ventricular enlargement and retrograde flow of the contrast agent into the IVC.

In cases of aortic dissection, narrowing the window can reveal a high-density area extending from the aortic root to the periphery of the pulmonary artery, suggesting aortic bleeding. Contrast agent makes the flap of dissection more visible, and it can be diagnosed as Stanford type A dissection. Pericardial hematoma as an indirect finding is important for both diagnosis and assessing severity.

In cases of open false lumen type and no calcification of the detached intima, it's difficult to diagnose. When aortic dissection needs to be ruled out, contrast-enhanced CT should be performed, they stated.

By narrowing the window, the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) becomes high-density. In contrast-enhanced CT, thrombus is observed and a decrease in contrast enhancement is evident in some portions of the intestinal tract. SMA embolism occurs when embolic material from the heart becomes lodged, so the thrombus is often found more than 5-8 cm distal to the branching point from the aorta. Pay attention to the blood vessels even in noncontrast CT. Thrombi should be observed by narrowing the window, according to the authors.

Important differentials for abdominal pain in women of reproductive age include ovarian hemorrhage, ovarian torsion, and ectopic pregnancy. Ovarian hemorrhage and ectopic pregnancy often involve the presence of an intraperitoneal hematoma as a diagnostic clue. However, telling if the ovary is enhanced or not isn't easy in the case of ovarian torsion, so it is crucial to track the vascular structures twisted at the ovary. It's important to find vascular structures toward the knot-like twisted segment, using thin slices and MPRs, they pointed out.

Gastrointestinal tract perforation can be fatal, especially for the elderly, so even when it isn't suspected clinically, always consider the possibility. Also, strangulation obstruction should be considered in all cases of acute abdominal pain, the authors wrote. Territorial bowel and mesenteric edema (TBME), which indicates venous congestion in the mesentery, is the early sign of intestinal ischemia. In coronal contrast-enhanced CT, bowel wall edema becomes more evident.

The symptoms and clinical findings are nonspecific in non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) and it can be fatal. Therefore, always look for indicators of the early stage of NOMI, such as intravascular dehydration (smaller SMV sign, collapse of IVC), dilatation of intestinal loops with the decrease of intestinal tonus and insufficient or patchy contrast enhancement of the intestines. However, it's important to be aware that the signs of intravascular dehydration may appear to be corrected by transfusion. Keep in mind the indicators of the early stage of NOMI, such as smaller SMV sign and collapse of IVC, they advise.

The co-authors of the presentation were Dr. Junichi Matsumoto (section chief of emergency and trauma radiology), Dr. Hikaru Ishida, Dr. Yukiko Michishita, and Dr. Hidefumi Mimura. You can view the full exhibit on the European Society of Radiology's EPOS website.